Fear ‘filled’ complication: intravascular hyaluronic acid filler injection and tissue necrosis

Published by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS)

Author Contributions

- Nicholas Jan Lichtenberg: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

- Nicholas James Otte: Conceptualization; data curation; writing – review and editing.

- Robert Choa: Conceptualization; data curation; writing – review and editing.

Intravascular injection and ensuing tissue ischaemia and necrosis is a recognized complication of injecting dermal fillers. Dermal filler treatments both in Australia and worldwide are increasing. From primary to tertiary care, rapid recognition and treatment of intravascular occlusion is critical to prevent complications such as tissue necrosis, scarring, visual impairment or blindness, and cerebrovascular events.

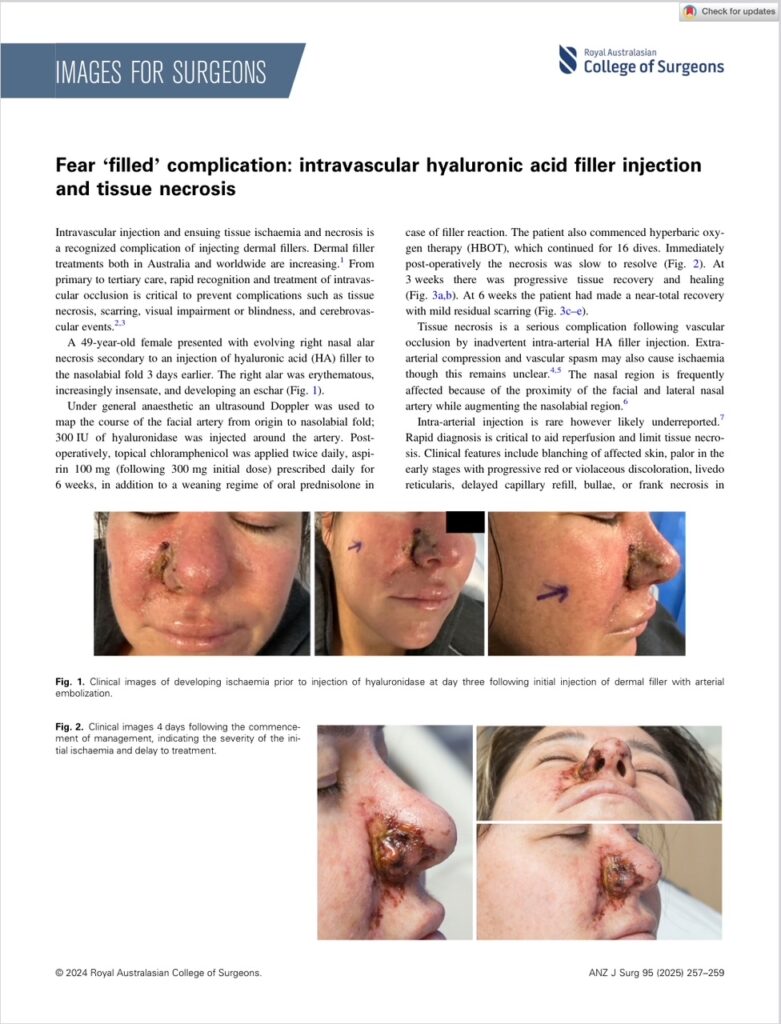

A 49-year-old female presented with evolving right nasal alar necrosis secondary to an injection of hyaluronic acid (HA) filler to the nasolabial fold 3 days earlier. The right alar was erythematous, increasingly insensate, and developing an eschar (Fig. 1).

Under general anaesthetic an ultrasound Doppler was used to map the course of the facial artery from origin to nasolabial fold; 300 IU of hyaluronidase was injected around the artery. Post-operatively, topical chloramphenicol was applied twice daily, aspirin 100 mg (following 300 mg initial dose) prescribed daily for 6 weeks, in addition to a weaning regime of oral prednisolone in case of filler reaction. The patient also commenced hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), which continued for 16 dives.

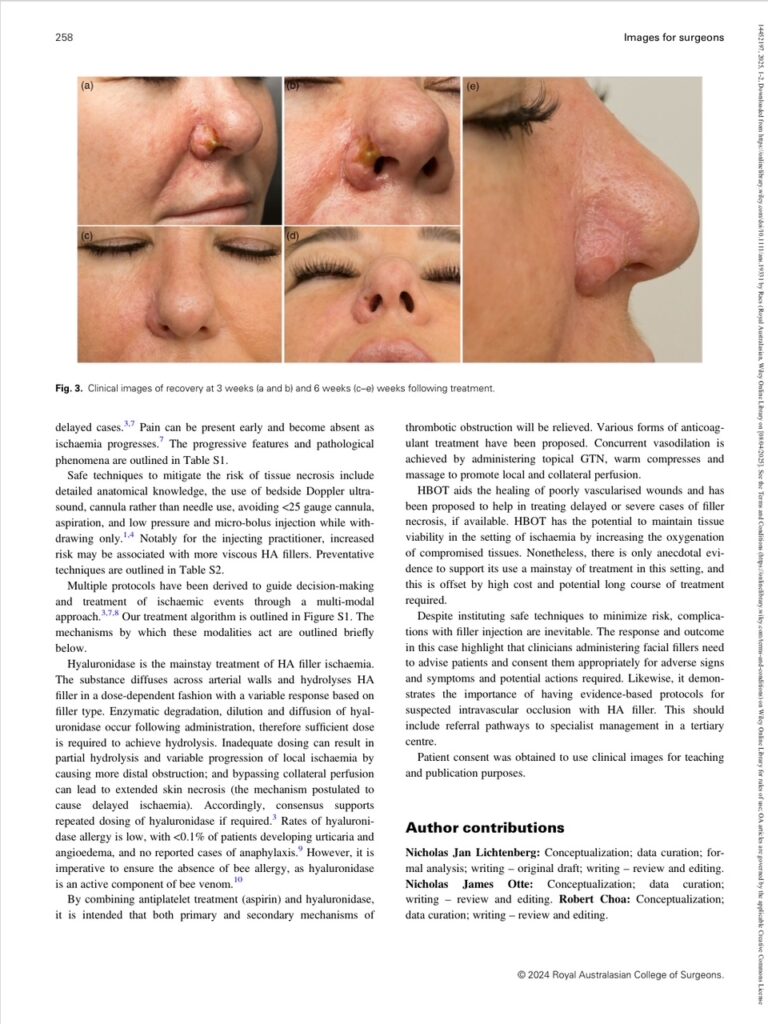

Immediately post-operatively the necrosis was slow to resolve (Fig. 2). At 3 weeks there was progressive tissue recovery and healing (Fig. 3a,b). At 6 weeks the patient had made a near-total recovery with mild residual scarring (Fig. 3c–e).

Tissue necrosis is a serious complication following vascular occlusion by inadvertent intra-arterial HA filler injection. Extra-arterial compression and vascular spasm may also cause ischaemia though this remains unclear. The nasal region is frequently affected because of the proximity of the facial and lateral nasal artery while augmenting the nasolabial region.

Intra-arterial injection is rare, however likely underreported. Rapid diagnosis is critical to aid reperfusion and limit tissue necrosis. Clinical features include blanching of affected skin, pallor in the early stages with progressive red or violaceous discolouration, livedo reticularis, delayed capillary refill, bullae, or frank necrosis in delayed cases. Pain can be present early and become absent as ischaemia progresses. The progressive features and pathological phenomena are outlined in Table S1.

Fig. 1. Clinical images of developing ischaemia prior to injection of hyaluronidase at day three following initial injection of dermal filler with arterial embolization.

Fig. 2. Clinical images 4 days following the commencement of management, indicating the severity of the initial ischaemia and delay to treatment.

Fig. 3. Clinical images of recovery at 3 weeks (a and b) and 6 weeks (c–e) weeks following treatment.

Safe techniques to mitigate the risk of tissue necrosis include detailed anatomical knowledge, the use of bedside Doppler ultrasound, cannula rather than needle use, avoiding <25 gauge cannula, aspiration, and low pressure and micro-bolus injection while withdrawing only. Notably for the injecting practitioner, increased risk may be associated with more viscous HA fillers. Preventative techniques are outlined in Table S2.

Multiple protocols have been derived to guide decision-making and treatment of ischaemic events through a multi-modal approach. Our treatment algorithm is outlined in Figure S1. The mechanisms by which these modalities act are outlined briefly below.

Hyaluronidase is the mainstay treatment of HA filler ischaemia. The substance diffuses across arterial walls and hydrolyses HA filler in a dose-dependent fashion with a variable response based on filler type. Enzymatic degradation, dilution and diffusion of hyaluronidase occur following administration, therefore sufficient dose is required to achieve hydrolysis. Inadequate dosing can result in partial hydrolysis and variable progression of local ischaemia by causing more distal obstruction; and bypassing collateral perfusion can lead to extended skin necrosis (the mechanism postulated to cause delayed ischaemia). Accordingly, consensus supports repeated dosing of hyaluronidase if required.

Rates of hyaluronidase allergy is low, with <0.1% of patients developing urticaria or angioedema, and no reported cases of anaphylaxis. However, it is imperative to ensure the absence of bee allergy, as hyaluronidase is an active component of bee venom.

By combining antiplatelet treatment (aspirin) and hyaluronidase, it is intended that both primary and secondary mechanisms of thrombotic obstruction will be relieved. Various forms of anticoagulant treatment have been proposed. Concurrent vasodilation is achieved by administering topical GTN, warm compresses and massage to promote local and collateral perfusion.

HBOT aids the healing of poorly vascularised wounds and has been proposed to help in treating delayed or severe cases of filler necrosis, if available. HBOT has the potential to maintain tissue viability in the setting of ischaemia by increasing the oxygenation of compromised tissues. Nonetheless, there is only anecdotal evidence to support its use as a mainstay of treatment in this setting, and this is offset by high cost and potential long course of treatment required.

Despite instituting safe techniques to minimize risk, complications with filler injection are inevitable. The response and outcome in this case highlight that clinicians administering facial fillers need to advise patients and consent them appropriately for adverse signs and symptoms and potential actions required. Likewise, it demonstrates the importance of having evidence-backed protocols for suspected intravascular occlusion with HA filler. This should include referral pathways to specialist management in a tertiary centre.

Patient consent was obtained to use clinical images for teaching and publication purposes.

© 2024 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.